Grief and Joy of a Wildcat Sighter

One evening at home in Costa Rica three years ago, I received an uncharacteristically excited call from my neighbor. “You would never believe this. There is a wild oncilla in my yard! It’s hiding underneath one of the bromeliads! It’s alive but not looking well. Come quick if you want to see one!” I flew out the door in seconds, all fired up and just as excited as my neighbor to see the most elusive and smallest of the country’s six wild cats.

I was completely smitten on first sight. It was no bigger than an average domestic cat, but what a spectacular coat of spots, including the belly! The small, delicate, winsome animal was semi-hidden under the vegetation. It made a tiny head motion when I carefully lifted the foliage, but otherwise remained silent and immobile. It was clearly moribund but had no sign of physical injury. We quickly took its photo, retreated, and observed it from a distance in the dark. The next morning, its body was found in exactly the same position. It had died sometime during the night. My neighbor buried it that same day. This was my one brief and sad introduction to the rare oncilla, my first in two decades.

Cat sightings at Nectandra are infrequent, but all six Costa Rican wild cats are present, known through casts of footprints (Fig 2), or camera trap images (Fig 3).

Our preserve is fronted by a sharp curve on a national highway. Occasionally, we saw injured animals hit by a car in front of our gate, as with the margay photographed (Fig 4 ).

By size, the six Costa Rican wild cats fall in three groups: the biggest are the jaguars and pumas (45 – 70 kg), ocelot and jaguarundi (11 – 13 kg) in the mid range, and the margay (2-5 kg) and oncilla the smallest (1.5 – 3 kg). I have seen two male jaguarundis in action, fighting on a tree after dark. They were impressively fierce, aggressive and making frightful noises. By size, coloration, the lack of spots, behavior, they were jaguarundis. I was certain they were not jaguars or pumas. Ocelot and margay (Fig 4), unfortunately, I have seen only as road kills in front of our gate. The smallest oncilla, known also as tiger cat, however, has been very elusive and rare. No one among our staff, whether on day or night duty, have seen one, dead or alive.

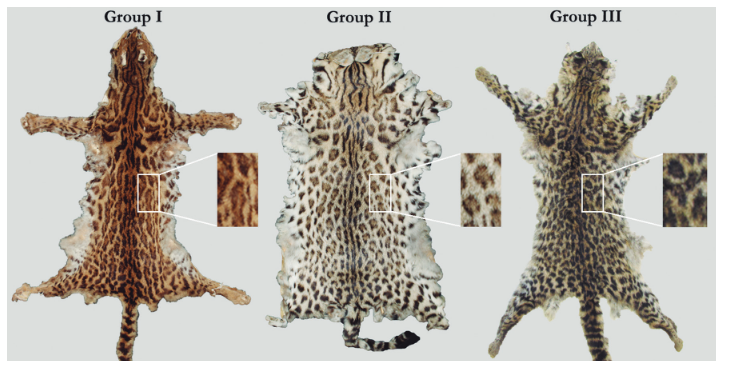

Given the small size of our sick cat, we excluded ocelot in the differential identification. But could it have been a margay? Margay has a longer tail (~1.5 X) in relation to its hind legs (Fig 4), whereas our cat’s tail was just slightly longer than its hind legs. Its coloration and spots were compatible with those described or seen in published photographs of tiger cats, we provisionally identified it as an oncilla. Armed with its photo and our brief observations made in the dark to aid in the identification, I went on a deep literature search for confirmation and more information.

It was obvious at once, from my reading, that among the American small spotted cats — the ocelot, margay and oncilla gave the experts the most difficulty. They shared overlapping geography, temporal distribution, and ecology. With slight variations, they overlap in sizes, are all spotted with rosettes and have similar coloration. In fact, expert mammalogists often could not tell them apart either, especially between the margays and oncillas. From late 1700’s onward to 2000’s, literally dozens of different specie names were attributed to one or both of the cats. Their taxonomy and phylogeny were unclear and remained in disarray until the advent of DNA technology.

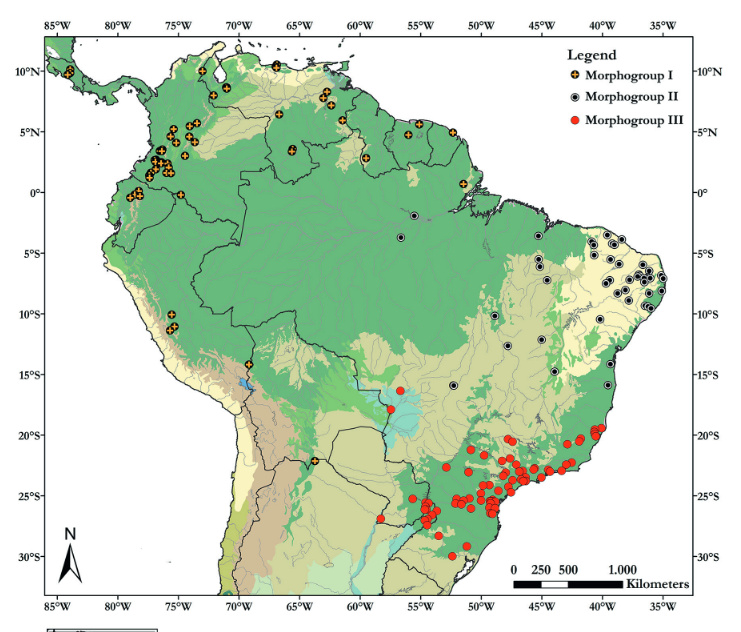

The low population density of oncillas was part of the problem. Sightings were spotty and infrequent. They are known from Costa Rica and Panama in the north, and in Columbia, Brazil, Bolivia in the south. Suitable specimens were few and far in between for comparative examinations. In one 2017 study, the authors were able to round up, from 23 museums in both Americas, only 250 skins and skull specimens to examine in detail. They analyzed the specimens’ associated geographic data, combined with careful skull measurements, survey of skin coloration, appearance of spots. Their results showed the distribution of the oncillas to be in 3 non-overlapping geographic groups (Fig 5).

http://dx.doi.org/10.11606/0031-1049.2017.57.19

Their pelts also showed discernible differences in coloration when compared side by side (Fig 6). The authors proposed three distinct morphologic groups I, II and III and were given names of I = L. tigrinus; group II = L. emiliae and group III = L. guttulus.

according to authors F Oliveira do Nacimiento and A Feijo.

Our sick oncilla, therefore belongs presumptively in the most northern tiger cat group, L. tigrinus, according to proposed taxonomic division of 2017. But even before that year was over, there were indications that newer results from more discriminating DNA technology did not fully align with the conventional taxonomy. The oncilla phylogeny was more complicated.

We are now in 2023 and information on oncilla biology is still changing and being modified at a rapid rate. New species of tiger cats are being discovered, via DNA technology, in Panama and Brazil. Relationships among the spotted cats are further being clarified, their geneology delineated and phylogeny realigned, as telltale signs of ancient interbreeding among them (margay and ocelot, oncillas and Geoffroy’s cats) are being discovered.

Ironically, while the small spotted cats are rare to scientific studies, they are not rare to the illicit animal fur trade. Between 1976 and 1985, an astonishing 350,000 L. tigrinus pelts were traded! The illegal hunting and fur trading has since decreased due to conservation awareness and anti hunting laws, but it has sadly not stopped.

Bonus brain teaser: On a totally different aspect of observing cats, did you know that a kitten can be both a solid and liquid? Yes, a liquid. This realization won Marc-Antoine Fardin, a physicist at Paris Diderot University, the Ig Nobel Prize 2017. As in the photo below, the kitty (not an oncilla!) “flows” into, i.e. assumes the shape of the stein, just as beer would!