The Revelation of Gustavo

Gustavo and his horde of relatives invaded Nectandra Reserve completely undetected. What snagged our attention was the defoliation of one tall Wercklea insignis tree (related to the Hibiscus family) with the dinner-plate size leaves. Under subterfuge, Gustavo and clan were eating the foliage nightly, but vanished by daylight. At first, the consumption was insignificant but gradually increased exponentially. Over the next two weeks, the culprits had become veritable feeding machines. The leaves were mowed at an astounding rate each night, but now the thieves were leaving an impressive amount of droppings on the ground by morning. Caterpillars! Judging from the size and appearance of the frass (insect poop), we knew they were from large moths, but which moth? There are some 5000 known ones in Costa Rica. Flightless, how could caterpillars disappear so completely each night? Easy. Hide in plain sight.

Once fingered, our caterpillars were spotted even in daylight. I felt utterly foolish and blind for missing them in the first place. There were many dozens of caterpillars of the same species, large as cigars, all aligned and with the exact coloration of the tree trunk! Immobile after their nocturnal feeding frenzy high up near the canopy, their striking tentacles were like beacons once we knew what to look for. Intrigued, my co-worker decided to adopt three selected specimens from the dozens. We wanted to follow the development to the end of their metamorphosis to identify them. Moths are identified morphologically from the adult and not the caterpillar stage. After transferring them to a large plastic container, the caterpillars were presented with fresh Wercklea leaves each night. Then we watched.

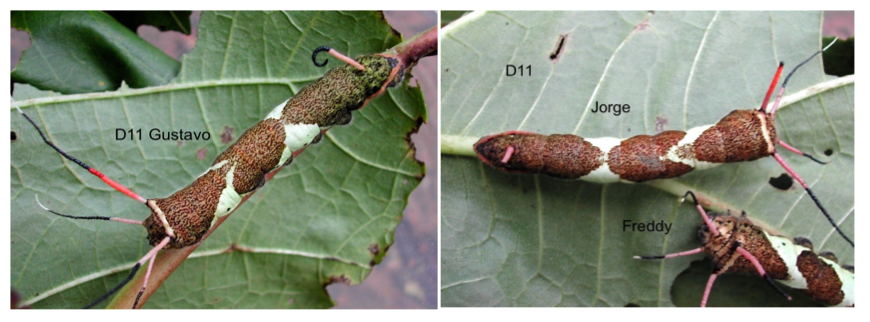

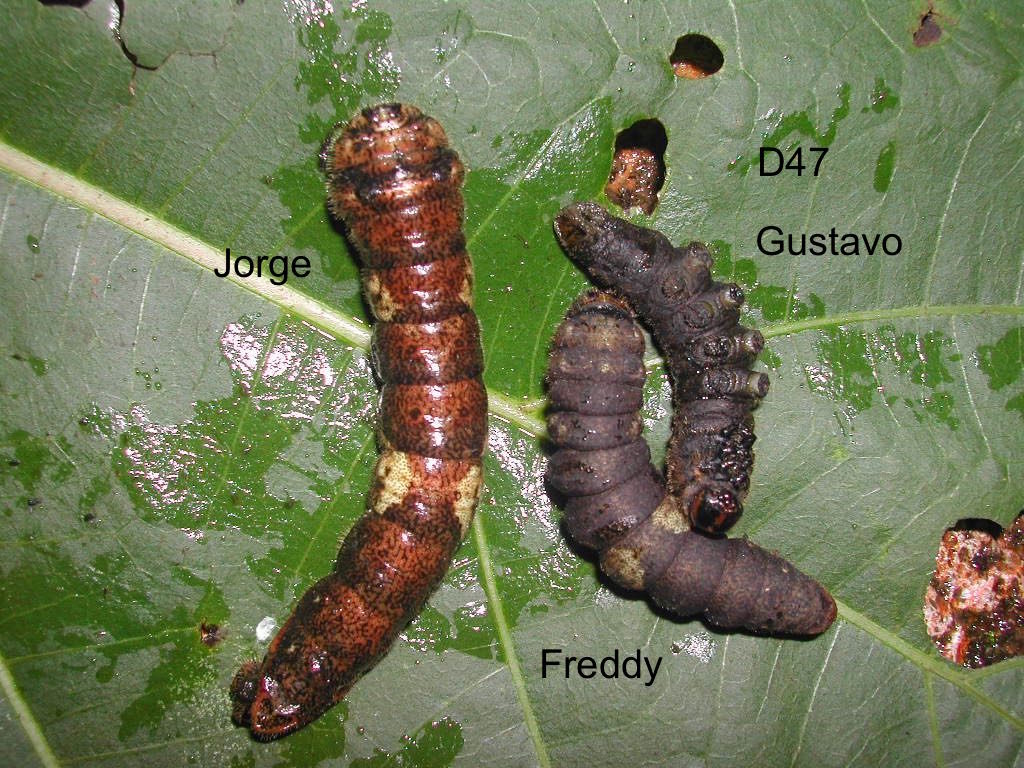

Naming the study subjects is a double-edged sword — a no-no among scientists for fear the anthropomorphism would cloud the observers’ judgment — but we couldn’t help ourselves. The handsomest of the three, we named Gustavo. He was already 10 cm in length (4in) not including his impressive head gear when we spotted him. He had 4 pink-black-white banded head tentacles on his head and one black-tipped pink (absolutely charming) curlicue on the tail segment. The photo of Gustavo below was taken on the first day (D1) of our study. Judging by its large size, Gustavo was probably already nearly full-grown.

We also chose two other fellow caterpillars to hedge against mortality during captivity. Jorge (right upper in photo below) was chosen because he had one distinctive broken left-head tentacle and Freddy was smallest in size. We needed a way to tell them apart.

By Day 11, Gustavo grew only slightly, but his spots were lighter in color, larger, sharper and more noticeable.

Right lower. Freddy

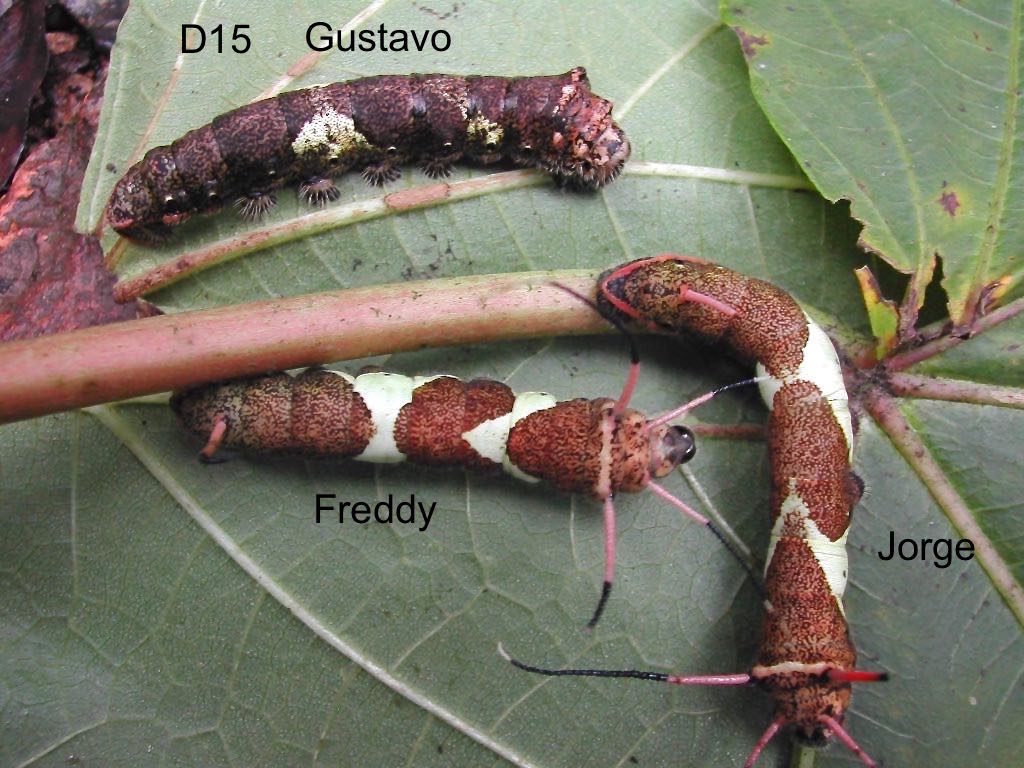

Four days later, D15, Gustavo shed its cuticle (skin) with the tentacles attached. He now looked very different. Its retractable head was beginning to enlarge, his spots fused and the triangular green patches faded. He was also acquiring a layer of fine facial hair. Jorge and Freddy in the meantime had not yet molted (photos below). The typical moth or butterfly sheds its skin 4-5 times. The stage in between each molt is known as an instar. The fourth or fifth instar is usually the final instar before it turns into a pupa if it is a moth, or chrysalis if it is a butterfly.

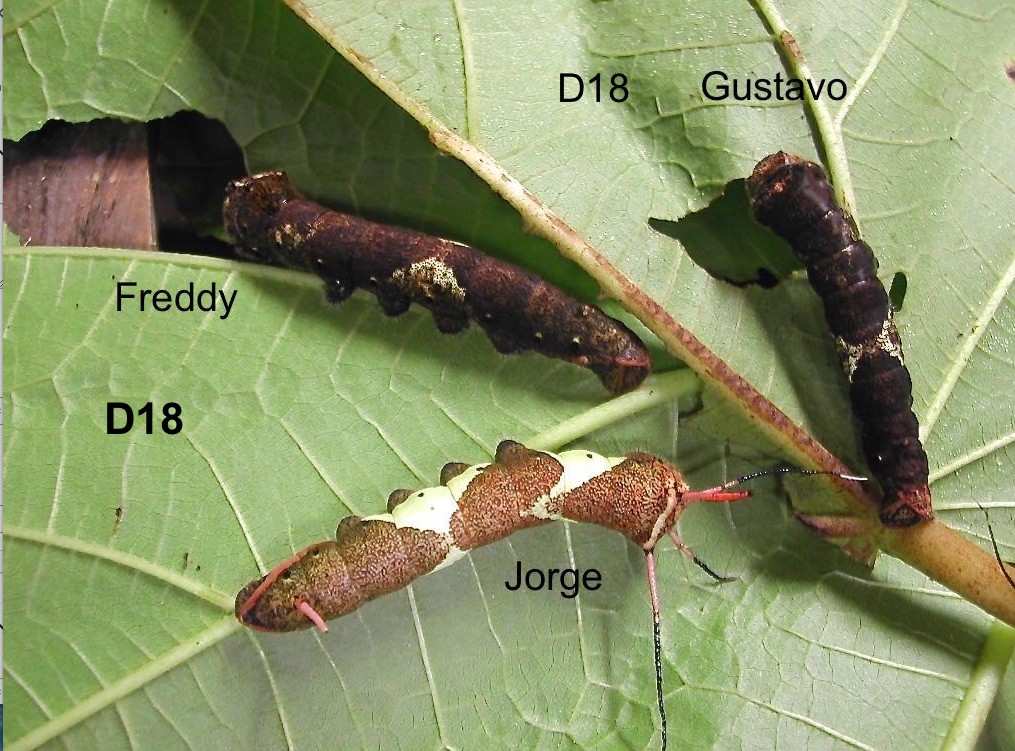

Things were now moving faster. By D18, Gustavo and Freddy were no longer eating. Both were shrinking in girth and length. Only Jorge still had his tentacles, was still feeding and growing.

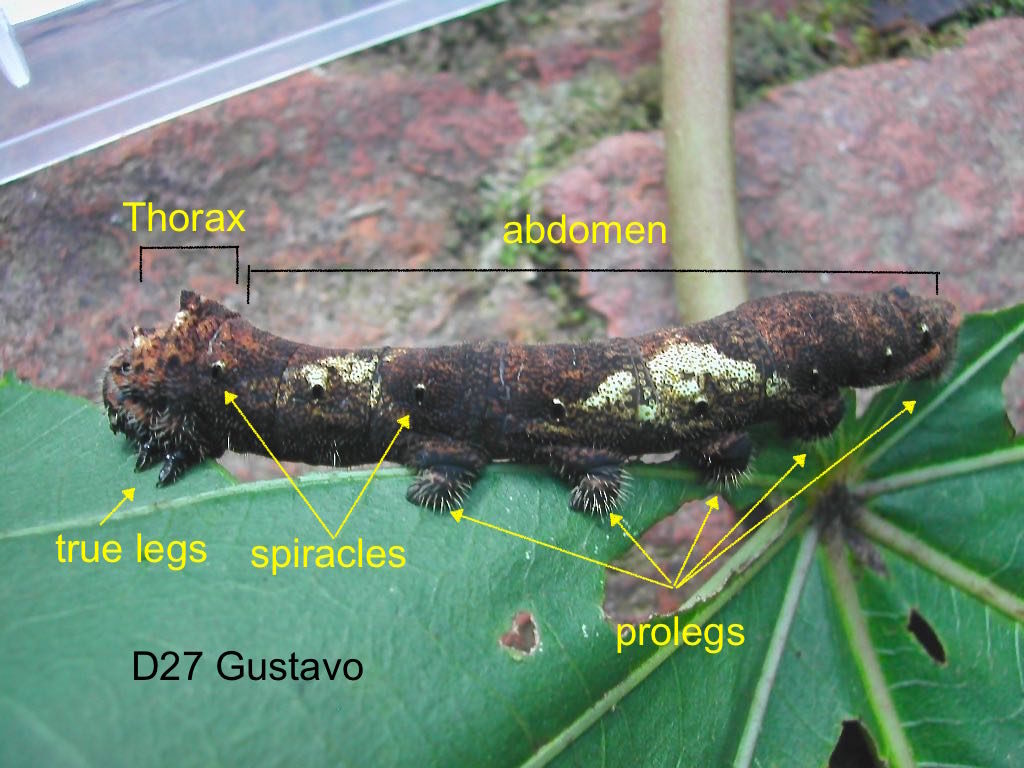

The photo of Gustavo on D27 revealed the classic body of caterpillars (next photo). First the head on the left is connected to the thin 3-segmented thorax, behind which is the thicker 10-segmented abdomen. The first three thoracic segments have three pairs of pointy, true legs, one pair per segment. These true legs help position the head while rasping the leaf during feeding. Thoracic segments 3,4,5,6,10 are equipped with pairs of prolegs (not jointed as the true legs). The muscular prolegs are equipped with clawed hooks for grasping. Anyone who has tried to dislodge caterpillars from their food plants knows how tenaciously the subjects can cling to the leaves.

Caterpillars have six single-lens eyes on each lower side of the head. These eyes can sense light intensity but do not form images. For respiration, they have a system of internal tubes and valves that end in spiracles (valves) on each side of the thoracic segment for gas exchanges (black dots in photo above visible on each segment). Inter-caterpillar communication is by deposition and emission of chemical trails. The caterpillars’ sensitivity to plant aromatics is incredibly efficient. I once witnessed a coordinated U-turn by a pack of 3 dozens caterpillars within seconds after I introduced fresh food plant within 15 cm (6 in ) of the lead caterpillar.

The next photograph (D27) below show the variation among their siblings not in captivity, still clinging to the tree. The narrow range in size indicated they were likely all hatched from eggs laid about the same time. Note the individual coloration and markings that allowed them to blend in the tree trunk —another example of the art of concealment mentioned in my previous blog. After all, they are sitting “ducks” at this stage, completely vulnerable to predation from birds, bats and parasitoid insects.

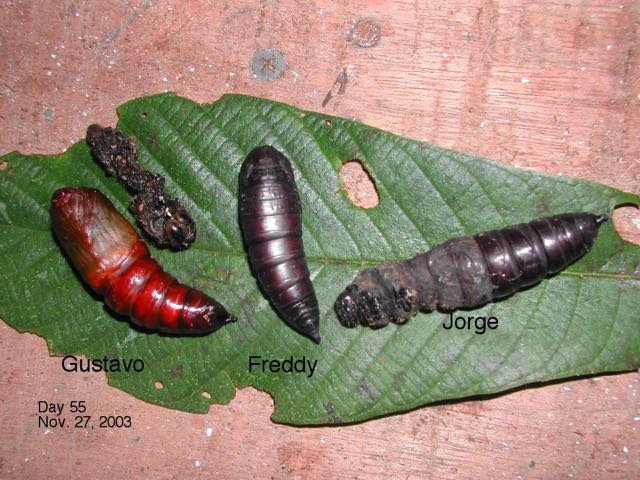

The formation of the pupae was pretty mysterious. Gustavo stopped feeding altogether shortly after D28. By D47, it has shrunk and hardened, but still with recognizable segments and prolegs. The photo below shows all three in the prepupa stage: Jorge was still caterpillar in form, whereas Freddy has started to pupate. Gustavo is still shrinking. By this point, the caterpillars had consumed enough nutrients and conserved enough water to last them through a complex series of transformation events to reach the terminal moth stage, most of which are not yet fully known.

The next image shows all three on D67. Gustavo was clearly a pupa showing hints of internal structure underneath the translucent exoskeleton, Freddy in the intermediate and Jorge in the semi-pupa stage.

At this point, not knowing the identity of our subjects meant we had to guess how to maintain the three pupae alive. Moth pupae are of two types: 1) naked pupae, usually found among leaves or soil or 2) in silk or spun cocoon. Since ours were of the first type, we put them in individual pots of loose soil and leaves. We then waited, and waited, and waited…

A full eight months later in October, resplendent Gustavo slowly and carefully emerged from the 5 cm pupa. Finally, we know what it is — a moth in the Saturniidae family, Arsenura batesii .

Gustavo had an impressive 13 cm (5in) wing span. Its body and wings were elegantly and spectacularly furry. The hair on moths are not truly hair, but modified scales that are also found on butterflies. The scales serve multiple functions, for thermoregulation, sex appeal, camouflage, and as expendable body structures during attacks. Nocturnal predators such as bats have been known to end up with mouthful of fur but not the prey.

This is where the decision to name our study subjects comes home to roost. Gustavo should have been named Gustava, a female, based on the thread-like antennae. The roving male saturniids have complex, feathered antennae, better to sniff out the mostly stationary, pheromones advertising females. Saturniids moths do not eat and have reduced mouth-parts. They only need to stay alive a couple of weeks — long enough to find a mate, and lay their eggs.

What is the benefit of metamorphosis? The most obvious is that the caterpillar and the adult moth occupy totally different niches. No competition between the old and the young. The two use different food sources, are totally different in forms, locomotions and phase duration. They are not subject to the same risks and vulnerabilities.

Our little exercise revealed only the stages between the last instar and pupa. We were not privy to the mysterious events behind the exoskeleton of pupae before moth emergence. The totally cloaked metamorphic events are just beginning to be unraveled. Thanks to micro-CT scanning adopted for the purpose of imaging interior events, we soon will have much more information of this astounding process.

It took us nearly a year’s observation to document one single caterpillar-moth pair. Imagine the colossal work of Dan Janzen (U of Pennsylvania) on 9000 moths in the last three decades in Costa Rica, not just their biology (photo below), but also DNA barcoding for final identification .